Sentoku Shuzo – The Only Brewery in Sunny Miyazaki Dedicated Exclusively to Sake

Blessed with the warmth of a southern climate, Sentoku Shuzo proudly continues to brew sake with unwavering dedication in Miyazaki—the only brewery in the region solely devoted to sake. Each day, we face the rice and water with sincerity, guided by the pride of being Miyazaki’s sole specialist in this traditional craft. Brewing sake is, in many ways, like raising a child. We begin with carefully selected sake rice and pure water from Nobeoka, a city that gazes out over the Hyuga-nada Sea. Our toji and kurabito work in harmony, nurturing each batch slowly and attentively, shaping a sake we come to regard as our own offspring. The world of fermentation is a living, breathing realm—where koji inhales and yeast dances. We stay close to the ever-changing moromi, day by day, never overstepping, yet never looking away. Like parents quietly watching over the growth of their child. And when that sake has finally matured, it begins its journey out into the world, bringing smiles to dining tables near and far. In imagining that scene, every effort, every painstaking step we took, feels worthwhile. We hope that each drop brings a gentle touch of color to your everyday life.

About Sentoku Shuzo

Founded in 1903, Sentoku Shuzo has been brewing sake for over 120 years. Located in Nobeoka, Miyazaki Prefecture—a region in southern Kyushu where shochu culture is deeply rooted—we remain steadfast in preserving the traditional methods of sake brewing to this day.

Although there are around 40 sake producers in Miyazaki, Sentoku Shuzo is the only one dedicated exclusively to brewing seishu, or Japanese sake.

The Beginning of Our Founding

The roots of Sentoku Shuzo trace back to 1903, when it was founded as Tsunetomi Shuzo Goshi Kaisha through the collective investment of a group of passionate individuals. Unusual for its time, the company adopted a non-family-owned model of management—an uncommon approach in the era’s sake industry.

From its inception to the present day, Sentoku Shuzo has not been tied to a single family lineage. Instead, it has passed down its craft and spirit through the hands of those driven by a genuine passion for sake. This inheritance of skill and dedication, rather than bloodline, remains the foundation of our brewery’s philosophy.

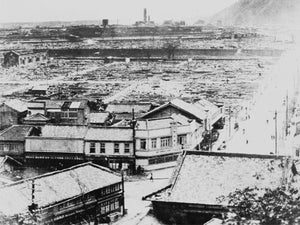

War and Reconstruction

However, on June 29, 1945, Nobeoka was devastated by a massive air raid that reduced most of the city to ashes. Sentoku Shuzo’s brewery, located near a major industrial site operated by Asahi Kasei Corporation, was completely destroyed in the blaze. Along with it, nearly all pre-war buildings and invaluable historical records were lost.

Yet just three years after the war’s end, in 1948, we began anew—rebuilding the brewery from the ground up on the very same site. It was the unwavering passion and conviction of our predecessors that made this rebirth possible. Their determination laid the foundation for everything we are today.

The Origin of "Sentoku"

Following postwar mergers and institutional reforms, the brewery was renamed Sentoku Shuzo Co., Ltd. in 1961. The name "Sentoku" (千徳), meaning “a thousand virtues,” carries a heartfelt wish: that those who drink our sake may be blessed with a thousandfold fortune and well-being. This sentiment continues to be passed down through generations.

Although official records from our founding were lost in the war, the spirit embodied in this name remains our guiding origin—a symbol of the values and hopes that have shaped Sentoku Shuzo since its earliest days.

Pioneering a New Sake Culture

In the 1980s, Sentoku Shuzo faced a difficult period with the rise of a competing sake brand launched by Asahi Kasei. Amid this challenge, we turned our attention to something still uncommon at the time: chilled sake.

While room temperature and warm sake were the norm, we recognized the potential of serving sake cold and were among the first to commercialize it. This bold move introduced a new way to enjoy sake—crisp, refreshing, and well-suited to modern palates.

Today, chilled sake is a staple, but one of its origins can be traced back to that pioneering effort by Sentoku Shuzo. It was a quiet revolution that helped reshape how sake is experienced, one glass at a time.

The Shochu Boom and the Present

In the 2000s, a nationwide shochu boom once again placed Sentoku Shuzo in a difficult position. As consumer preferences shifted, sake breweries across Japan faced declining demand—and ours was no exception.

Even so, we continued to persevere. Today, under the leadership of President and toji (master brewer) Kadota, our team of just five dedicated members works together to sustain the spirit and craft of our small brewery. Every bottle we produce is the result of their shared commitment, resilience, and pride in carrying on the legacy of sake in Miyazaki.

The Pride of Brewing Sake in the Tropical South

In Japan, there remains a strong perception that the best sake comes from colder regions. As a result, many people are unaware that sake is even brewed in the warm southern climate of Miyazaki.

Despite this, Sentoku Shuzo has continued to craft sake in the tropics—without relying on family succession, but instead passing down skills and passion from one generation of brewers to the next. Confronting the challenges of a different climate and cultural landscape, we have held fast to our belief in the potential of sake.

It is this quiet determination, forged not in the snow country but under southern skies, that defines who we are.

Sake Nurtured by the Waters of Nobeoka

In the past, Nobeoka was home to many sake breweries. One of the key reasons was its abundant supply of pure water, drawn from sources such as the Gokase River, which originates in the sacred land of Takachiho.

Though located in Japan’s warm southern region, Nobeoka offered an environment remarkably well-suited to sake brewing. With its clear, plentiful waters and natural surroundings, this land quietly nurtured a sake tradition that defied geographical expectations.

Commitment to ingredients

Sentoku’s sake is brewed using premium sake rice varieties such as Yamada Nishiki and Hanakagura, cultivated under contract within Miyazaki Prefecture. These carefully grown local grains form the foundation of our flavor.

The water used in brewing comes from the subterranean streams of the Gokase River, which originates in the sacred highlands of Takachiho. This pure, mineral-rich water meets the fragrant rice to create high-quality daiginjo and a diverse range of expressive sake.

It is this union of local rice and pristine water that gives Sentoku its depth, elegance, and unmistakable sense of place.

Koshimizu Cultivation

Koshimizu Cultivation is an eco-friendly farming method developed in Koshimizu Town, Shari District, Hokkaido. It centers around the use of a unique liquid material called Koshimizu Liquid, made from deep ocean water. When combined with composted manure from cattle and pigs, this method harnesses the power of organic microorganisms to grow crops without relying on chemical fertilizers.

By enhancing the soil’s natural vitality, this approach promotes healthier plants and a more sustainable agricultural cycle. Rice grown using Koshimizu Cultivation has been highly praised for its quality—earning the distinction of being selected as imperial rice for presentation to the Japanese Imperial Household in 2015.

The power of microorganisms and minerals

At the heart of Koshimizu Cultivation lies the dynamic interplay between microorganisms and minerals. Microorganisms break down organic matter and fertilizers in the soil, transforming them into forms that are more easily absorbed by plants as nutrients.

Minerals, on the other hand, play a crucial role in stimulating microbial activity—especially actinomycetes, a group of beneficial bacteria. This activation energizes the entire soil ecosystem, enhancing its vitality and resilience.

As a result, rice plants grown under this method develop their natural immunity, gaining stronger resistance to pests and disease. The outcome is mineral-rich, vigorous rice that reflects the health of both the land and the cultivation process itself.

Vegan Certified

Sentoku Shuzo practices fully vegan-friendly brewing, using no animal-derived ingredients whatsoever. This means that meat, seafood, eggs, dairy products, honey, and any other animal-based substances are completely excluded from our production process.

At present, our Sarasara Nigori has officially received vegan certification. However, all of our sake is made using the same ingredients and brewing standards, ensuring that every product we offer is suitable for those following a vegan lifestyle. With purity and transparency at the core of our philosophy, our sake can be enjoyed with confidence by all.

Our Vision for the Future

At Sentoku Shuzo, we continue to embrace new challenges while honoring the tradition and craftsmanship passed down for over a century. With deep gratitude toward the farmers who grow our sake rice, we strive to draw out the fullest expression of aroma and flavor from every single grain. From our warm southern home in Miyazaki, we are committed to sharing sake that can be loved around the world. This is not only our pride—it is our unwavering mission, now and into the future.

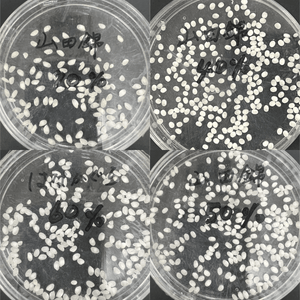

Seimai (Rice Polishing)

At Sentoku Shuzo, the first step in sake brewing is seimai (rice polishing). This important preparation involves carefully milling away the outer layers of the rice grain, leaving primarily the inner starch at the core.

The outer layers of brown rice contain proteins, fats, and other components that are less suitable for sake production. By removing these parts and retaining only the ideal portion of the rice, we create a foundation for sake with a clean, delicate aroma and flavor—free from unwanted impurities.

Washing and Soaking (Senmai and Shinseki)

After polishing, the rice undergoes the crucial steps of washing (senmai) and soaking (shinseki), essential preparations that greatly influence the flavor of the sake.

For rice polished to 70%, washing is performed using specialized machines. However, more delicately polished rice—at 60%, 50%, or even 40% polishing ratios—is carefully washed entirely by hand. This is because the higher the polishing rate, the more fragile the rice becomes, requiring precise control over water absorption.

Following washing, the rice is soaked for a carefully timed duration. Soaking (shinseki) demands second-by-second accuracy because even the slightest variation in water absorption can affect fermentation progress and, ultimately, the sake’s taste.

In this intense and meticulous process, the toji (master brewer) and kurabito (brewery artisans) work closely together, communicating constantly and synchronizing their efforts. This harmony, born from the intuition and teamwork of skilled craftsmen, cannot be replicated by machines. It is here that the true spirit of sake brewing resides.

Steaming

At Sentoku Shuzo, the soaked rice is carefully steamed over approximately 50 minutes—a process that holds great importance in sake brewing.

Steaming transforms the starch within the rice, preparing it for optimal fermentation. It also sterilizes the rice by eliminating unwanted bacteria through heat, ensuring a clean environment for brewing.

The goal is to achieve gaikō-nainan (外硬内軟)—the ideal steamed rice texture where the outer layer is firm while the inside remains soft and fluffy. This balance of firm exterior and tender interior is crucial for every step that follows.

For example, during koji production, the soft inner rice allows the koji mold’s filaments to penetrate deeply, nurturing fragrant and flavorful koji. In the subsequent stages of yeast starter (shubo) and main mash (moromi), the rice dissolves at an appropriate pace—not too quickly or too slowly—enabling smooth fermentation.

Because the steaming condition profoundly influences the final taste of the sake, Sentoku Shuzo treats this process with meticulous care and dedication, never sparing effort or time.

Koji making

In sake brewing, there is a saying: “One koji, two moto, three tsukuri,” emphasizing that the most important step is koji making. This process cultivates the “core” of sake, determining its flavor, aroma, and depth.

Koji is made by sprinkling koji-kin (Aspergillus oryzae), a beneficial microorganism, onto steamed rice and allowing it to grow. This mold converts the rice starch into glucose through a process called saccharification, creating the foundation for fermentation. Because of this, the quality of the koji directly influences the quality of the sake.

At Sentoku Shuzo, koji is carefully nurtured over two full days in a dedicated koji room (kojimuro) maintained at around 30°C.

On the first day, cooled steamed rice is brought into the koji room in a process called hikikomi. The rice is then loosened, spread out, and its temperature and moisture are precisely adjusted. The ideal steamed rice texture here is gaikō-nainan—firm on the outside and soft on the inside—because the koji mold seeks moisture and grows best by penetrating the inner rice.

Once prepared, the next step is tanekiri, where koji spores are evenly sprinkled over the rice and gently mixed to coat every grain. The rice is then piled into a mound and wrapped in cloth to maintain high humidity, creating an optimal environment for the koji mold to germinate and multiply.

This meticulous process sets the stage for producing fragrant, flavorful koji—the essential “heart” of sake.

Koji making - continued

On the second day, as the koji begins to develop its aroma, the rice grains start to clump together, much like rice left overnight. The morning’s first task is kirikaeshi, where the koji is gently broken up and stirred to even out the temperature throughout.

Next comes mori, shaping the koji into an even thickness to stabilize its growth. Around midday, an intermediate step called nakashigoto is performed—spreading the koji layers wider to allow air circulation and eliminate temperature variations.

In the evening, the final step called shimai-shigoto takes place. At this stage, the koji emits a subtle chestnut-like fragrance and tastes slightly sweet when chewed. The heated koji is spread out to release excess heat and gradually dry the surface.

After several hours, the core temperature of the koji stabilizes around 40–43°C. The moisture content is carefully checked and adjusted, preparing for the final stage of cultivation.

Completion is assessed on the morning of the third day. Skilled brewers evaluate the aroma, flavor, texture, and hazekomi—the degree to which mold filaments have penetrated each grain. When the koji shows a perfect balance of fragrance, sweetness, and firmness, it is considered finished.

Each tiny grain of this carefully nurtured koji becomes the foundation for fermentation, aroma, and flavor in the sake that follows. At Sentoku Shuzo, sake brewing begins with this uncompromising, painstaking cultivation of koji.

Moto (Yeast Starter) Making

In sake brewing, there is a traditional saying: “Ichikoji, Nimoto, Sansukuri” — meaning “first koji, second moto (starter mash), third brewing.” This phrase highlights the critical importance of moto preparation following koji making.

The moto—also called shubo—is a small fermentation starter where yeast, the vital agent of sake fermentation, is carefully cultivated. It is literally the “mother of sake,” nurturing the life source for the entire brewing process.

At Sentoku Shuzo, we create a cradle for yeast in specially designed small tanks dedicated to moto production. Into these tanks, we combine koji, steamed rice, water, yeast, and lactic acid. Using a long stirring paddle called a kaibō, brewers gently mix the contents while carefully controlling the tank’s temperature and overall condition.

Maintaining a uniform temperature and mixture throughout the tank is crucial. The feel of the paddle in the mash and even slight temperature differences profoundly affect yeast development. Since yeast is a living organism, we meticulously monitor and adjust the temperature every day, nurturing the yeast over approximately two weeks.

At Sentoku Shuzo, the rice and yeast used for moto vary depending on the sake being produced. Even with the same ingredients, each shubo is unique—never showing the exact same characteristics twice.

Because of this, our brewers sharpen all five senses to observe the slightest changes daily. The resistance felt when stirring, subtle temperature shifts, aromas rising from the tank—these small insights are carefully accumulated to guide the moto toward its ideal state.

Moto making is a quiet, delicate dialogue with the tiny life of yeast. The care and sincerity invested at this stage influence every aspect of the later fermentation, aroma, and flavor of the sake.

Moromi (Main Mash) Brewing

The pinnacle of sake production is moromi brewing—the main fermentation mash. At this stage, koji, steamed rice, and water are added to the yeast starter (shubo) to advance fermentation in earnest.

Sentoku Shuzo follows the traditional “three-step addition” method, known as sandanjikomi. Instead of adding all ingredients at once, they are introduced gradually over four days in three separate stages. This careful approach prevents the yeast from becoming diluted too quickly and helps inhibit the growth of unwanted bacteria.

By protecting the yeast’s strength and gradually creating an optimal fermentation environment, this method embodies centuries of brewing wisdom.

Day 1: Soe-zukuri (First Addition)

The process begins by adding a small amount of koji, steamed rice, and water to the yeast starter. The mash is kept at around 12°C, allowing the yeast to gently adapt and start fermentation without stress.

Day 2: Odori (Rest Day)

No ingredients are added on the second day, known as the odori or “dancing” day—a pause that allows the yeast to build momentum. The term comes from the “landing” or resting place on a staircase, symbolizing a moment to catch one’s breath.

During this crucial time, brewers carefully stir with a kaibō (stirring paddle), monitoring the rice’s dissolution, texture, temperature, and overall fermentation progress. This rest period is essential for yeast proliferation and setting the stage for the next steps.

Moromi Brewing – Continued

Day 3: Naka-zukuri (Second Addition) — Regulating Fermentation

On the third day, known as naka-zukuri, approximately twice the amount of koji, steamed rice, and water compared to the first addition is added to the mash. At this stage, the mash temperature is lowered further to around 8°C. Considering the warm southern climate of Miyazaki, the brewing water is cooled to near 0°C before use.

This careful temperature control helps manage yeast activity, allowing the fermentation to develop steadily and smoothly.

Day 4: Tome-zukuri (Final Addition) — Completing the Moromi

The final stage, called tome-zukuri, involves adding roughly twice the amount of ingredients used in the second addition, bringing the mash volume to its maximum.

The temperature is lowered further to about 6°C, and ice may be added directly as needed to maintain this cool environment. To keep the mash uniformly mixed, brewers stir vigorously using their whole body.

Throughout this process, temperature is closely monitored to prevent over-fermentation. Final adjustments are made to guide the sake toward its ideal quality.

Wisdom and Technique in the Brewing Process

By nurturing the moromi over four days through the stages of soe (first addition), odori (rest), naka (second addition), and tome (final addition), the yeast’s strength is maximized, resulting in clean, balanced sake without unwanted off-flavors.

At Sentoku Shuzo, skilled brewers carefully balance temperature and fermentation based on climate and raw material conditions, adjusting by sight and touch.

This delicate, hands-on process—where one can almost hear the heartbeat of the fermenting mash—is at the very core of our sake brewing tradition.

Shibori (Pressing)

After carefully nurturing the moromi (fermentation mash) for one to one and a half months, it finally transforms into sake through the process called josō—or shibori—the pressing stage.

Shibori is the work of gently squeezing the moromi to separate it into genshu (undiluted sake) and sake kasu (sake lees). Much like pressing juice from fruit, this moment concentrates all the layers of rice, koji, water, and fermentation that have blended and matured over time.

As they carry out pressing each day, the toji (master brewer) and kurabito (brewery workers) sense the condition of the sake through its subtle “presence” inside the tanks. With utmost care and patience, they press slowly—never rushing, always mindful not to damage the sake they have cultivated.

When the pressing is complete, a quiet relief washes over the team—a delicate blend of tension and joy, a fleeting moment only those artisans know. This final step marks the emergence of sake from the living mash into the clear, refined beverage ready to be shared.

Sentoku Shuzo Co., Ltd.

2-1-8 Osecho, Nobeoka City, Miyazaki 882-0841, Japan

Phone: +81-982-32-2024

President: Kenji Kadota

Founded: 1903 (Meiji 36)

Monday to Friday: 9:00 AM – 5:00 PM

Closed: Saturdays, Sundays, and public holidays

Water Source

The Gokase River, originating from Takachiho—the Land of the Gods

The water from Takachiho, known as the “Land of the Gods,” has long been revered as sacred and is featured in ancient Japanese mythology. The Gokase River, fed by this pure water, has been recognized as one of Japan’s cleanest rivers for eleven consecutive years in national water quality surveys.

Thanks to this abundant, pristine water, sake brewing has flourished for generations in Nobeoka City, Miyazaki Prefecture. Since about 80% of sake is composed of water, high-quality water is essential for producing delicious sake.

Sentoku Shuzo, located in Nobeoka, uses the clear underground spring water (known as fukuryusui) from the Gokase River as its brewing water. Despite Nobeoka’s relatively warm, southern climate, this abundant pure water helps maintain precise temperature control during fermentation, especially for the moromi mash, supporting the production of high-quality sake.

For the breweries of Nobeoka, this exceptional water is truly a treasured resource.

Rice Origin — Takachiho Area

Takachiho Town, Nishiusuki District, Miyazaki Prefecture

Takachiho Town in Miyazaki Prefecture is a lush mountainous region known as the “Land of the Gods.” Its most notable feature is the significant temperature difference between day and night. This wide temperature range, combined with the pristine water of the Gokase River—ranked among Japan’s best in water quality—slowly brings out the rich flavor of the rice, cultivating high-quality sake rice.

Sentoku Shuzo uses Yamada Nishiki rice, contract-grown in Takachiho, for its Daiginjo Koyo and Junmai Daiginjo Yume no Nakamade. The Hanakagura variety, also from Takachiho, is used in Takachiho Kenjoshu ”Mai”. These rice varieties impart a clear, refined character unique to the Takachiho region, enriching the sake’s overall quality and distinctiveness.

Rice Origin — Takaharucho area

Takaharu Town, Nishimorokata District, Miyazaki Prefecture

Takaharu Town in Miyazaki Prefecture lies at the foot of the majestic Kirishima mountain range and is known as one of the region’s premier rice-producing areas, blessed with abundant natural spring water.

A defining feature of Takaharu is the widespread use of a unique local farming method called Koshimizu Cultivation. This approach enriches the soil by harnessing beneficial microorganisms such as Koshimizu bacteria, while minimizing the use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides to maximize the natural strength of the rice.

Rice grown through Koshimizu Cultivation is highly regarded for its distinctive sweetness and rich, complex flavor. In Takaharu, premium sake rice varieties like Yamada Nishiki—known as the “king of sake rice”—and Miyazaki’s original Hanakagura are carefully cultivated using this method.

Sentoku Shuzo pays special attention to rice from Takaharu, using it to brew sake such as Hokura Sentoku, which is crafted from rice nurtured in this very land.