Kobayashi Shuzo Honten

Our brewery is nestled in the rich natural surroundings of Umi Town in Kasuya District, on the outskirts of Fukuoka City, where mountains and rivers shape the landscape. Since our founding in 1792, during the Kansei era of the mid-Edo period, we have upheld a steadfast commitment to brewing truly delicious sake. For eight generations, the Kobayashi family has passed down this tradition with care and pride. The second-generation head, Kappei, came into possession of a curious stone resembling an aged turtle. Inspired by the Japanese saying “a turtle lives for ten thousand years,” the family chose the name Bandai—meaning “eternity”—as the signature name for our sake. In 1898, the sixth-generation head, Sakugorō, was awarded a prestigious gold medal at the National Sake Competition. That honor was followed by an imperial envoy dispatched on behalf of the Emperor Meiji, a rare and deeply respected recognition. Since then, our sake has continued to earn numerous top honors at various competitions and expositions. Though we remain a small-scale brewery, we take great pride in preserving traditional techniques and crafting each bottle with meticulous care. We brew using premium sake rice varieties such as Yamada Nishiki and Yumeikkon, grown in Fukuoka Prefecture, and we rely on the pristine waters of the Sangun mountain range. With a strong focus on local ingredients and heritage, our sake reflects the spirit of Fukuoka. We invite you to experience the unique character of our handcrafted sake—born from tradition, nature, and dedication.

The Origin of Our Sake: Rice from Fukuoka

In sake brewing, selecting the right rice is as vital as choosing the right grapes in winemaking. It is a foundational step that shapes both the quality and the character of the final product. Our insistence on using rice grown in Fukuoka Prefecture stems not merely from the convenience of sourcing locally, but from a deeper desire to express the unique spirit of this land and our enduring connection to it.

Fukuoka has long been recognized as a prominent sake-producing region. In particular, the Chikugo area, with its fertile soils nourished by the abundant waters of the Chikugo River, has a history of cultivating excellent sake rice. The Itoshima district, meanwhile, is celebrated as a major production area of Yamada Nishiki—widely regarded as the finest sake rice in Japan.

Choosing rice from Fukuoka means infusing each drop of our sake with the breath of the local land and its agricultural soul. The distinct character imparted to the rice by Fukuoka’s climate and terrain is then refined and elevated by the skill of our toji (master brewer), culminating in sake that truly embodies its place of origin.

Our mission is singular: to capture the essence of Fukuoka in our sake—to create a flavor experience that could only be born of this land. What we strive to express is nothing less than the taste of Fukuoka.

The Heart of Our Sake Brewing: Yamada Nishiki from Itoshima

Often hailed as the “King of Sake Rice,” Yamada Nishiki has earned its title for good reason. Only sake brewed from this exceptional rice possesses the unparalleled elegance, layered complexity, and radiant aroma that distinguish it from all others. It is especially indispensable for crafting highly refined styles such as daiginjo.

Ideal Yamada Nishiki displays several hallmark qualities: large grains with a clearly defined white core known as shinpaku, low protein content that minimizes off-flavors, and consistent size and weight for optimal polishing and brewing performance. However, despite its stellar reputation, Yamada Nishiki is notoriously difficult to cultivate. Its tall stalks are prone to lodging (falling over), yields are often unstable, and the plant itself has limited resistance to disease. These challenges mean that suitable growing regions are scarce, and farmers must devote exceptional care and effort to managing the soil, water supply, and pest control.

That is precisely why we continue to use Yamada Nishiki grown in Itoshima—one of Japan’s most esteemed regions for premium sake rice—for our highest-grade offerings, including daiginjo and junmai daiginjo. Our decision reflects a clear commitment to quality: even in the face of high costs and cultivation difficulties, we refuse to compromise.

We hold deep respect for the unmatched quality of Itoshima-grown Yamada Nishiki and consider it well worth the investment. Just as importantly, we treasure the strong partnership we’ve built with the dedicated contract farmers in Itoshima who grow this rice with great care and expertise. This philosophy lies at the very heart of our sake brewing.

Yumeikkon: Fukuoka’s Native Sake Rice and Its Unique Appeal

Born from the expertise and dedication of the Fukuoka Agricultural Research Center, Yumeikkon is a sake rice variety unique to Fukuoka. In the field, it offers several key advantages: the stalks are sturdy and resistant to lodging, making cultivation easier and yields more stable. At the same time, it possesses the high grain quality necessary for sake brewing—an impressive feat that stands in stark contrast to the famously delicate Yamada Nishiki. Yumeikkon is, in many ways, a testament to Fukuoka’s advanced agricultural capabilities.

In the brewery, this rice demonstrates equally remarkable characteristics. It absorbs water quickly and allows koji mold to propagate efficiently, which helps unlock the full depth of the rice’s umami. The resulting sake carries a fruity aroma alongside a rich, satisfying expression of rice flavor. On occasion, a pleasant bitterness on the finish adds structure and complexity, creating a dynamic and well-rounded taste experience.

We primarily use Yumeikkon for brewing junmai ginjo and junmai sake, where its full-bodied umami and distinctive character can truly shine. Within our lineup, it holds a role as vital as that of Yamada Nishiki. While Yamada Nishiki brings the refinement and elegance essential to our highest-end sakes, Yumeikkon contributes depth, structure, and individuality to our core offerings.

By using these two Fukuoka-born sake rice varieties in complementary ways, we are able to showcase the full breadth of local expression. This approach reflects both our deep respect for tradition and our pride in the land we call home—values we strive to infuse into every glass of sake we craft.

Tsukushi Homare: Fukuoka-Grown Rice That Brews Everyday Deliciousness

When it comes to our honjozo and futsushu—meant to be enjoyed casually every day—we never compromise on the quality of our ingredients. For the base rice in these everyday brews, we’ve chosen Tsukushi Homare, a variety grown here in Fukuoka Prefecture. This rice offers key advantages for cultivation: it’s sturdy, resistant to lodging, and delivers consistently stable yields.

To be sure, Tsukushi Homare does not boast the aromatic elegance of the “King of Sake Rice,” Yamada Nishiki, nor does it have the distinctive character of Yumeikkon. It tends not to develop a prominent shinpaku (white core), and while it’s not highly rated as a table rice either, its strength lies elsewhere. Its reliability in the field and its ability to produce a gentle, honest sake profile make it ideal for the kind of sake we envision—something comforting and delicious, meant to accompany the everyday meal.

While it may not steal the spotlight, Tsukushi Homare plays an essential supporting role—like the quiet foundation that holds everything together. This is why we proudly use locally grown rice even in our most accessible offerings. It's a reflection of our commitment not just to flavor, but to the land, the people, and the quality that defines every drop of sake we make.

The First Step to Refining Sake Quality: The Importance of Rice Polishing and Outsourcing to Specialists

In sake brewing, rice polishing—or seimai—is one of the most fundamental yet crucial steps. It involves carefully milling away the outer layers of brown rice—bran, proteins, fats, and other components—to reveal the starchy core known as shinpaku. These outer layers contain elements that can lead to off-flavors and interfere with the clean aromas produced by yeast during fermentation. By polishing the rice, brewers can access the pure starch needed for smooth fermentation and refined flavor.

The extent of polishing is expressed as the seimaibuai (rice polishing ratio), which indicates the percentage of the grain remaining after milling. For example, a seimaibuai of 60% means that 40% of the outer portion has been removed. The lower the number, the more the rice has been polished. This process significantly influences the style and quality of the final sake.

Generally speaking, highly polished rice (lower seimaibuai) results in sake that is light, aromatic, and elegant—typical of ginjo and daiginjo styles. In contrast, less-polished rice retains more of its natural character, leading to richer, fuller-bodied sake with a pronounced umami profile.

At our brewery, we entrust this vital step to Kyushu Howa Co., Ltd., a specialized milling company. Using both manual and automated polishing machines, they tailor the process to the unique attributes of each rice batch—taking into account factors like variety, origin, grade, and harvest year—to precisely achieve the polishing ratios we require. They also conduct thorough foreign matter removal, maintaining consistently high standards of quality and accuracy.

Because seimai demands advanced technology and plays such a decisive role in determining the final flavor, we’ve made the strategic choice to outsource this process. By partnering with a dedicated specialist equipped with state-of-the-art machinery and deep expertise, we ensure a level of precision and consistency that exceeds what we could achieve in-house. This collaboration contributes significantly to the overall quality and character of our sake.

Precise Moisture Control: The Critical Role of Washing and Soaking

Even after the rice has been polished, fine layers of nuka (rice bran) still cling to its surface. This bran contains proteins and lipids that can lead to off-flavors in the final sake, which is why the next step—senmai (washing)—is crucial. During this process, the rice is meticulously washed to remove these residual impurities. Thanks to its vital role in enhancing purity, washing is often referred to as the “second polishing.”

Following senmai comes shinseki, or soaking. This step allows the rice to absorb water in preparation for steaming, which gelatinizes the starch—a transformation known as alpha conversion. This process makes the starch much easier for koji enzymes to break down into sugars.

However, precision is critical. If the rice absorbs too much water, it becomes overly soft when steamed, making it difficult to cultivate good koji. Conversely, insufficient water uptake can leave the rice undercooked at the core, resulting in a firm center—or shin—that hinders fermentation.

This balance is especially delicate when working with highly polished rice, such as that used for daiginjo sake, which absorbs water at a rapid rate. In such cases, soaking times must be managed with extreme precision—sometimes down to the second. Achieving the optimal moisture level requires not only accumulated data but also the keen judgment of experienced brewers. Every second counts when shaping the foundation of a refined sake.

Automating the Rice Washing Process: Advancing Precision and Quality

At our brewery, we have adopted advanced washing and soaking equipment manufactured by MJP, including their automated “rice-washing robot.” This system features full automation of weighing, washing, and water control, along with innovative mechanisms that deliver uniform washing while conserving water. It also ensures rapid drainage of turbid water, effectively suppressing undesirable bran odors. Maintenance is simple and efficient.

By integrating this specialized technology, we have significantly improved the consistency and reproducibility of our rice preparation, even when processing large volumes. Operational efficiency has also increased dramatically.

Although washing and soaking may appear simple at a glance, they are foundational steps that greatly influence the downstream processes. By minimizing the variability that comes with manual work, we can consistently prepare rice in its ideal state. This is a clear example of how modern technology can be strategically utilized to stabilize and enhance sake quality.

Koshiki and Steamed Rice: A Tradition Passed Down Through Generations

After soaking (shinseki) and draining, the rice moves on to the next critical stage: steaming, known as mushimai. The purpose of mushimai is threefold—gelatinizing the starch through heat (a process called alpha conversion), sterilizing the rice, and achieving the ideal texture for sake brewing: gaikō-nainan—firm on the outside, soft on the inside.

At our brewery, we use a traditional steaming vessel known as a koshiki. In this method, steam is channeled from the kettle into the bottom of the koshiki, rising through the layers of rice to cook it evenly. The steaming process typically takes about one hour, with careful adjustments to steam pressure throughout. Unlike the continuous steamers used in many large-scale breweries today, the koshiki represents a time-honored approach that we continue to uphold.

The cultural importance of the koshiki is also reflected in the term koshiki-daoshi, which marks the final steaming of the brewing season. This vessel has long been regarded as a symbol of traditional sake-making.

We believe that steaming with a koshiki produces rice with the ideal gaikō-nainan texture—an essential quality for proper koji cultivation and smooth fermentation. While this method requires more time and effort than modern machinery, it allows for subtle, precise adjustments that are simply not possible with continuous steamers. For us, using a koshiki is not about resisting efficiency, but about preserving the craftsmanship and heritage that define sake brewing.

This choice reflects our deep respect for tradition, artisanal skill, and the enduring legacy of sake-making.

Koji and Haze: How the Cultivation of Koji Shapes the Soul of Sake

Koji mold (Aspergillus oryzae) is considered the very heart of sake brewing—a vital microorganism without which sake would not exist. Its primary role is to produce two crucial enzymes: amylase, which converts starch into fermentable sugars, and protease, which breaks down proteins into amino acids that contribute to umami. Since yeast cannot directly consume starch, the work of koji mold is essential for initiating fermentation.

The process of cultivating koji, known as seikiku, begins by inoculating a portion of the steamed rice—typically about 20% of the total—with koji spores. This rice is then carefully nurtured in a dedicated, climate-controlled room called the kojimuro, where temperature and humidity are strictly regulated.

The quality of the resulting koji significantly affects the final profile of the sake—its flavor, aroma, depth, and structure. What makes koji cultivation particularly intricate is that not only are there many strains of Aspergillus oryzae, but the manner in which the mold is grown into the rice—called haze—also greatly influences the strength and type of enzymes produced.

There are two main types of haze (mold propagation styles), each suited to different sake styles:

① Sōhaze (total haze)

This type features mold filaments that densely cover the rice grain and penetrate deep into its core. It generates a high concentration of enzymes for both starch and protein breakdown, making it ideal for full-bodied, umami-rich sake such as junmai-shu.

② Tsukihaze (point haze)

Here, mold appears sparsely on the surface but grows deeply into specific contact points. It results in milder enzymatic activity, particularly reduced protein breakdown, helping to suppress unwanted flavors. This makes it well-suited for elegant, refined sake such as ginjo-shu.

Rather than simply applying koji mold, brewers carefully select the strain and meticulously manage how it grows—tailoring the enzyme balance to suit the desired flavor profile. Through this fine-tuned control, they determine whether the finished sake will emphasize richness and umami or focus on clarity and delicacy. This nuanced art of koji-making lies at the core of sake's diversity and depth.

Diverse Shubo Techniques: Employing Medium-Temperature and High-Temperature Saccharification Starters

The shubo—also known as moto, or the “mother of sake”—is a critical step in sake brewing. As its name suggests, it serves as the foundation for fermentation, where a small amount of select yeast is carefully cultivated under safe and controlled conditions to multiply into a powerful, active starter for the main mash (moromi). This mixture begins with steamed rice, koji, water, and a small quantity of high-quality yeast.

A key element in this process is the creation of a strongly acidic environment using lactic acid. Whether through traditional methods like kimoto, where naturally occurring lactic acid bacteria generate the acid over time, or modern sokujo methods, which add food-grade lactic acid directly, the goal is the same: suppress unwanted microbes while allowing sake yeast to thrive and multiply.

The cultivation period varies by method—about two weeks for sokujo, and around a month for traditional kimoto or yamahai styles. Regardless of the method, a healthy, robust shubo is essential for smooth fermentation and ultimately determines the flavor, aroma, and balance of the finished sake.

At our brewery, we use both the chūon shubo (medium-temperature starter) and kōon tōka shubo (high-temperature saccharification starter) methods. The kōon tōka approach involves raising the temperature to around 55°C at the beginning of the process to rapidly convert starch into sugar, followed by rapid cooling. This drastically shortens the starter’s development period to just about seven days. In contrast, chūon shubo is maintained at an intermediate temperature—between standard sokujo and kōon tōka—offering a balanced alternative.

By using both methods selectively, we can adapt to the production schedule and tailor our brewing approach to the flavor profile we aim to achieve. The kōon tōka shubo is efficient and lends itself to clean, crisp sake, while the chūon shubo can foster more nuanced yeast activity and the generation of aroma precursors under specific conditions.

This flexibility in our starter preparation reflects our broader philosophy: to carefully engineer each stage of brewing—beginning with the shubo—to align with the final vision for the sake.

The Classic Three-Step Brewing Method – and the Distinctive Fourth Addition

Shikomi refers to the main fermentation phase in sake brewing, where the yeast starter (shubo), koji, steamed rice (mushimai), and water are combined in a large fermentation tank to begin producing the sake mash, known as moromi. At our brewery, we primarily employ the traditional sandanjikomi (three-stage brewing) method—a time-tested technique developed to ensure safe, balanced, and flavorful fermentation.

In sandanjikomi, ingredients are added gradually over four days in three separate stages: hatsuzoe (first addition) on day one, followed by a rest period known as odori on day two, nakazoe (second addition) on day three, and tomezoe (final addition) on day four. This staggered approach allows us to carefully control the acidity and yeast concentration inside the tank, minimizing the risk of bacterial contamination while promoting healthy yeast propagation.

This method is not only foundational to Japanese sake brewing but also highly logical—ensuring a safe fermentation process while maintaining the delicate balance between saccharification (starch-to-sugar conversion) and fermentation. Our adherence to sandanjikomi reflects our commitment to consistency and high-quality fermentation management.

In addition to this standard method, we also use yondanjikomi (four-stage brewing) for select products. This technique involves adding an extra portion of steamed rice, typically near the end of fermentation. The goal is to intentionally retain more residual sugars, resulting in a sake with a fuller body, smoother texture, and richer sweetness. The finished product often exhibits enhanced complexity and depth, with pronounced notes of sweetness and richness.

We apply yondanjikomi selectively when crafting sake styles that aim for a rounder, more indulgent profile. By skillfully combining the foundational sandanjikomi with the optional yondanjikomi, we are able to tailor our brewing techniques to match the flavor vision of each product. This flexible approach underscores our philosophy of adapting the craft to best suit the character and intent of every sake we create.

Four Key Indicators of Sake Quality: Interpreting the Moromi

Throughout the fermentation period—and all the way up to pressing—we closely monitor the condition of the moromi (main mash) through daily analysis. This careful observation allows us to track the fermentation process with precision and adjust our approach as needed to ensure optimal results. The key indicators we measure include the following:

① Alcohol Content

This represents the percentage of alcohol produced by yeast during fermentation. In the moromi stage, alcohol levels typically reach between 14% and 20%. Alcohol content directly influences the body and perceived weight of the sake on the palate. By law, sake must have an alcohol content below 22%.

② Sake Meter Value (SMV)

Also known as nihonshudo, this measures the specific gravity of the mash relative to water. A lower (negative) SMV indicates higher residual sugar and a sweeter profile, while a higher (positive) SMV reflects lower sugar and a drier profile. This metric helps gauge how much sugar the yeast has consumed.

③ Acidity (San-do)

This value reflects the total amount of organic acids—such as lactic acid, succinic acid, and malic acid—produced by the yeast and koji. Higher acidity results in a sharper, drier impression, while lower acidity tends to yield a softer, rounder flavor. Acidity is essential for balancing overall taste.

④ Amino Acid Content

This measures the concentration of amino acids, primarily derived from the breakdown of proteins by koji. A higher amino acid level generally enhances umami, richness, and depth. In ginjo-style sake, brewers often aim for lower amino acid levels to achieve a cleaner, more refined taste.

These four indicators are invaluable for understanding not only whether fermentation is proceeding as expected, but also the kind of flavor profile that is emerging. By analyzing these metrics, we gain insight into yeast activity, sweetness-dryness balance, acidity structure, and umami potential.

At our brewery, we combine precise scientific data with generations of hands-on experience. This data-driven approach to fermentation management ensures that we consistently deliver sake of the highest quality, exactly as we intend.

Pressing and Sake Lees Ratio: Pursuing Quality Through Every Drop

Jōsō refers to the pressing stage in sake brewing, where the fermented mash (moromi) is separated into liquid—clear sake—and solids known as sake kasu (sake lees). At our brewery, we utilize two main methods for this crucial process: the efficient Yabuta-style automatic press and the more delicate fukuroshibori, or “bag pressing,” which collects only the drops that naturally drip out without applying any mechanical pressure.

Different stages of the pressing process yield distinct sake profiles:

① Arabashiri

The free-run sake that flows naturally before any pressure is applied. It is often youthful and exuberant, with a vibrant, aromatic character.

② Nakadori (or Nakagumi)

The central portion extracted under moderate pressure. This is the most balanced and refined part of the batch, often selected for competition entries or premium products due to its superior harmony of aroma and flavor.

③ Seme

The final portion obtained by applying stronger pressure. While it can contain a higher concentration of flavor components, it also tends to carry more roughness and potential off-notes.

Pressing yields more than just clear sake:

- Genshu

This is the undiluted sake that comes straight from the press, with an alcohol content typically around 18–20%. It retains the full strength and richness of the original brew. - Sake Kasu (Lees)

These are the solid remnants left after pressing. Rich in nutrients and umami, sake kasu is often used in cooking, fermentation, and even cosmetic products.

An important metric related to pressing is the kasu-buai—the ratio of sake lees to the weight of the white rice used. At our brewery, this often exceeds 30%, which is relatively high. This is characteristic of ginjo-style brewing, where a cleaner, more refined flavor is achieved at the cost of lower liquid yield. It reflects our commitment to quality over quantity, with a focus on producing sake of exceptional clarity and balance.

Balancing Flavor and Stability: Choosing Between Pasteurization and Nama-Storage

Once the sake is pressed during jōsō, the resulting liquid—often in its undiluted form (genshu)—typically undergoes filtration followed by a period of maturation. These stages play a vital role in refining and stabilizing the final product.

Filtration (Roka)

This step usually takes place relatively soon after pressing. Its primary purpose is to remove fine solids, resulting in a clearer, more polished appearance. In some cases, activated charcoal may be used to subtly adjust the color or aroma. Filtration contributes to a clean, stable sake profile, both visually and in taste.

Maturation (Jukusei)

The filtered sake is stored in tanks or other vessels for a designated period, allowing flavors and aromas to mellow and integrate. This resting phase helps bring harmony to the overall character of the sake.

In conjunction with maturation, most sake undergoes hiire—a heat treatment designed to stabilize quality:

Hiire (Pasteurization)

Sake is gently heated, typically to 60–65°C, to deactivate enzymes and eliminate microbes such as hi-ochi bacteria. This process helps prevent unwanted changes during storage and distribution, ensuring product consistency.

One variation of hiire is:

Namachozō (Single Pasteurization)

Here, the sake is stored in its unpasteurized (nama) form and pasteurized only once, just before bottling. This method aims to preserve the fresh, vibrant character of nama-zake, while providing a baseline level of stability.

The choice between the standard two-time pasteurization and namachozō significantly influences the final flavor. Two-time pasteurization maximizes shelf stability but may slightly alter the aromatic profile. In contrast, namachozō retains a fresher, more lively impression, closer to that of raw sake, while still offering a degree of protection.

Our use of both approaches reflects our flexible, product-specific mindset. Whether prioritizing stability or freshness, we tailor our maturation and stabilization techniques to suit the character and intent of each individual sake. This balance between tradition and adaptability is central to the sake we strive to create.

Two Finishing Styles: Pasteurized Sake and Namagenshu

At last, we come to the final stage before our sake reaches your hands. At our brewery, we employ two primary finishing methods, depending on the product.

① Standard Finishing: Dilution and Pasteurization before Bottling

After maturation, the genshu (undiluted sake) is adjusted with water to reach a more approachable alcohol content—typically around 15–16%. This process, known as warimizu, balances the flavor and makes the sake smoother and easier to enjoy. If needed, a second pasteurization (bin-hiire) is carried out before bottling. This is the most common approach used for sake available on the general market.

② Bottling as Nama Genshu (Unpasteurized, Undiluted Sake)

Some of our offerings are bottled without any dilution or heat treatment. These are high-alcohol, unpasteurized sakes that retain the raw, unfiltered essence of freshly pressed sake. This style delivers a bold, vivid expression of flavor with a vibrant and dynamic character. However, it is extremely delicate and must be kept under strict refrigerated conditions to maintain quality.

By offering both styles—standard pasteurized sake and nama genshu—we aim to meet the diverse preferences of our customers. Diluted and pasteurized sake is easy to enjoy and widely accessible, while nama genshu appeals to seasoned sake enthusiasts seeking purity, power, and freshness in every sip.

Through these tailored finishing techniques, we can craft distinct personalities from the same base sake—ensuring our products resonate with both casual drinkers and devoted connoisseurs alike. This flexible, customer-focused approach lies at the heart of our sake-making philosophy.

Kobayashi Shuzo Honten - Rice polishing ratio and classification of designated sake

| Designation | Rice Variety Used |

Required Polishing Ratio

|

| Junmai Daiginjo | Itoshima-grown Yamada Nishiki | 50% or less |

| Daiginjo | Itoshima-grown Yamada Nishiki | 50% or less |

| Junmai Ginjo | Yamada Nishiki, Yume Ikkon | 60% or less |

| Ginjo | Yume Ikkon | 60% or less |

| Tokubetsu Junmai | Yume Ikkon |

60% or less or Special Brewing Method

|

| Junmai | Yamada Nishiki, Yume Ikkon | No regulation (*) |

| Tokubetsu Honjozo | Yume Ikkon |

60% or less or Special Brewing Method

|

| Honjozo | Tsukushi Homare | 70% or less |

| Futsushu (Table Sake) | Tsukushi Homare | No regulation |

This table clearly illustrates the relationship between the types of rice we use and the polishing ratio requirements that are essential for each sake classification.

It shows how terms like “Daiginjo” are directly connected to specific rice polishing processes and their respective ratios.

Kobayashi Shuzo Honten Co., Ltd.

2-11-1 Umi, Umi-machi, Kasuya-gun, Fukuoka 811-2101, Japan

Phone: 092-932-0000

President: Hiroshi Kobayashi

Company Established: November 1986

Founded: Kansei 4 (1792)

Monday to Friday, 8:00 AM – 5:00 PM

Closed on Saturdays, Sundays, and National Holidays

Water Source

三郡山系

The brewing water that supports sake production at Kobayashi Shuzo Honten comes from the underground streams of the Sangun mountain range, located near Umi Town. This water is renowned as “meisui,” or famous water, known for its purity and exceptional quality. It is classified as soft water, which is considered ideal for sake brewing.

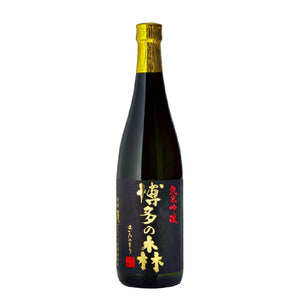

Sake brewed with soft water typically has a gentle mouthfeel and a smooth, mellow flavor. For example, “Hakata no Mori,” one of Kobayashi Shuzo Honten’s flagship sakes, is crafted using this water and is recognized for its refined and pleasant texture. By combining this pristine water with carefully selected sake rice from Fukuoka Prefecture, Kobayashi Shuzo Honten remains dedicated to pursuing truly delicious sake.

The pure water of the Sangun mountains is truly an essential element in creating the high-quality sake for which Kobayashi Shuzo Honten is known.

Yamada Nishiki Production Region

Itoshima Peninsula

Yamada Nishiki grown in the Itoshima region is widely regarded as the “King of Sake Rice.” This area benefits from the abundant waters of the Sefuri mountain range, providing ideal conditions for cultivating sake rice. Yamada Nishiki is characterized by its large grains and a prominent, starchy core known as “shinpaku.” Because it contains low levels of protein and fat, it produces sake with a clean, refined flavor and minimal unwanted notes.

This rice also has excellent water absorption, making it easy to create high-quality koji. As a result, it brings out the natural umami and sweetness of the rice, contributing to sake with an elegant, delicate aroma and a full, well-balanced taste. Yamada Nishiki is also able to withstand high levels of polishing, which makes it indispensable for brewing premium sakes such as Daiginjo.

Itoshima-grown Yamada Nishiki, nurtured by skilled brewers, serves as the foundation for crafting unique and high-quality sake that truly expresses the character of both the rice and the region.

Yumeikkon Production Region

Chikugo area

Yumeikkon, primarily cultivated in the Chikugo region, is the first sake rice variety independently developed by Fukuoka Prefecture. It was bred from Yume Tsukushi, a well-known Fukuoka table rice, and is recognized for its adaptability to the local climate and ease of cultivation. Compared to Yamada Nishiki, Yumeikkon plants are shorter, making them less likely to fall over and more resistant to typhoons and other weather events, which ensures stable harvests for farmers.

Sake brewed with Yumeikkon is typically light, crisp, and refreshing, with a clean finish. Its gentle aroma and smooth, unassuming character make it a perfect choice as a food-friendly sake that pairs well with everyday meals. Yumeikkon also absorbs water quickly and promotes efficient starch conversion by koji mold, making it a highly workable sake rice for brewers.

Nurtured by the rich natural environment of the Chikugo region, Yumeikkon gives Fukuoka sake its approachable and distinctive personality.